A new suit can help someone land a job – and give them confidence moving forward in life. For the HOPE program, a new suit is just one of the many benefits participants get.

The Helping Offenders Prosper through Employment (HOPE) Mentoring program was adopted by the Indiana Department of Correction in 2015, though the HOPE research team has existed since 2011. HOPE was developed by Theresa Ochoa, Associate Professor in Special Education, when she learned that many students with disabilities were incarcerated in juvenile correctional facilities. As she began looking into the school-to-prison pipeline and factors that contribute to incarceration and recidivism, the idea for the HOPE Mentoring program was born.

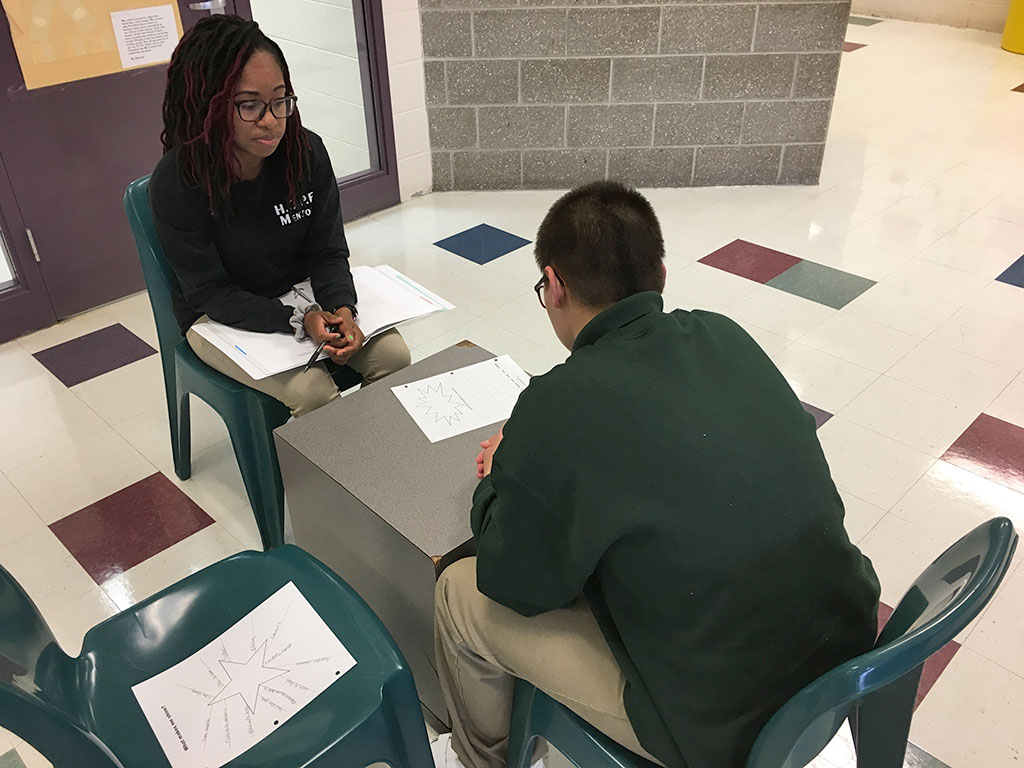

Mentors within the program provide weekly 1-1 support to incarcerated youth that focuses on developing employment skills. Each mentor comes up with individualized activities for their assigned mentee, so activities can vary depending on the needs of the students, with most activities circling back to employment. Mentors help mentees fill out job applications and write resumes and cover letters. They also create mock interviews and help with goal setting and developing tangible steps to reach those goals. Sometimes the focus is on soft skills like teamwork, respect or strong communication by journaling, conversation or reading. For other sessions, mentors and mentees enjoy a relaxed activity plan doing a Sudoku puzzle or playing a game as they build their relationship.

“Research shows that one of the greatest protective factors against recidivism is employment, which makes sense,” Ochoa explained. “Everyone needs money and without a job, some youth are forced to turn to illegal options to get money. But finding employment requires resources which many students simply don’t have. Sometimes those resources are tangible, like an appropriate outfit to wear for a job interview. Other times, the resources are less concrete but no less important, such as having a support system to lean on during the job search process, or having the confidence to apply for a job.”