Edu-Thinker Influence and Expertise Rankings 2025

Policy Report #25-B • May 2025

Authors

Prof. Christopher Lubienski, Prof. Joel Malin, Paul Faulkner, Kristin Schumacher

Key Takeaways

- Think tanks and similar organizations continue to play a prominent, even outsized role in education policy discussions.

- In many cases, there is a disconnect between the influence of some organizations (and the individuals they employ) and the expertise they bring to the table.

- There are also a notable number of cases where the influence of these organizations (and the individuals they employ) is relatively proportionate to their expertise.

- Conservative-leaning organizations (and individuals therein) are well-represented at the top of the rankings of influence, while rankings of expertise show a more ideologically diverse picture.

- Policymakers and the media still need to be vigilant as to the ideological agendas of these types of knowledge brokers claiming to represent the research evidence.

In the United States – and increasingly, across the globe – think tanks and similar organizations hold a prominent position in policy discussions. Especially in some areas where knowledge is more technical, or policies are more contested, as in education policy, policymakers often look to think tanks and similar knowledge brokers to gather (if not produce), package, and translate relevant research and evidence to inform policy discussions.

Because they play such a crucial function, it is worth asking about how the technical expertise of these organizations, and the people who work at them, supports or undercuts their influential role as key knowledge brokers.

Originally, this project was inspired by a similar exercise, where a think tank has sought to rank university-based scholars on their influence. Interestingly, such rankings of higher education faculty are based largely not on what is valued in universities — things like grant-writing, advising doctoral students, or publishing in prestigious journals or academic presses. Instead, those rankings measure university-based scholars on things that are typically prized by think-tanks — things like book sales or being mentioned in the Congressional Record or in news media or on the internet.

So, our original thought was to turn the tables and measure think tanks based on the scholarly factors valued by academics: degree attainment, publishing in exclusive scholarly outlets, citations to their scholarly work, etc. And we also realized there is another important factor at play here. University-based scholars may or may not be expected to be influential, but they certainly are expected to have expertise in their areas. This led us to compare and contrast the influence of think tanks (and the individuals who work in them) with measures of their expertise.

In our previous report on this issue, we found some notable disconnects in those regards. We noted that, in an ideal world, one might hope that the knowledge brokers most equipped to understand and interpret research evidence would also be the most influential in policy discussions. Indeed, since policymakers, funders and others had been calling for “what works” and “evidence-based policy,” we might hope that they then pay the most attention to organizations and individuals who best understand research and evidence.

But too often that was not the case. Indeed, in many instances, our inaugural (2024) report highlighted organizations that exerted substantial influence, but that had relatively little research expertise. Thus, it appeared that much of their influence was due to media and networking acumen in promoting a particular ideological agenda, rather than to an empirical or analytical grounding. Furthermore, it should be noted that the elevation of influence over expertise might be expected in an era that has seen a decline in — and even concerted attacks on — experts.

This year’s report too often tells a similar story. In our rankings of influence and expertise, we identify examples of some organizations and individuals that enjoy significant influence, but their influence is not necessarily grounded in empirical acumen. At the same time, we see instances of high-capacity organizations, with highly trained and accomplished experts, that have far less impact on education policy discussions.

For this latest edition of our report, we also added a new element: the ideological persuasions of these organizations (and, by extension, the experts — or “experts” — they employ). Using publicly available, independent classifications and indicators of political leanings, we looked at patterns of prominence for organizations representing different ideological agendas. We found that measures of expertise present a relatively balanced representation of different political leanings. But when looking at influence, conservative organizations are quite well-represented in the rankings, and this was even more true with individuals who work at such organizations — indicating that those organizations are adept at hiring and/or nurturing individuals who come to be known for their influence, if not for their expertise in many cases.

Together, these findings suggest the need for caution on the part of policymakers, the media, and public regarding information from many of these organizations. There are some organizations that appear to be “honest brokers” in that they have levels of expertise that undergird their notable influence in education policy. But quite often there are organizations, particularly on the conservative end of the spectrum, that enjoy substantial influence, although they do not seem to have commensurate expertise that one might assume to be necessary to support the agendas they are (often aggressively) pushing.

Approach

As with the previous edition of this report, this project utilizes measures of influence and scholarly expertise, drawing on publicly available data. The underlying purpose is to understand the extent to which different think tanks exert influence in discussions of education policy issues, and the degree to which their influence is supported by actual expertise on those areas (as opposed to, say, simply driven by an ideological agenda). Furthermore, this year we also consider the political leanings of different organizations in order to explore patterns of ideological inclinations in shaping those discussions.

For this project, we take a somewhat open view of the idea of “think tanks” in order to include similar organizations that operate in this space of promoting evidence for policymaking purposes. Certainly, we include organizations that fit the classic conception of a think tank, such as the Brookings Institution and the Heritage Foundation, and that seek to offer evidence to inform discussions of education policy issues. But we also include more recent entrance into this space, such as ExcelinEd and the Network for Public Education (NPE). Notably, some of the organizations we include, such as the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) or New America, have broad portfolios that span multiple issues, including education, while others, such as All4Ed and the Learning Policy Institute (LPI), focus primarily on education issues. We also look at individuals employed within these different types of organizations whose work focuses on education issues.

Here, we examine some 198 individuals working in education policy at 28 different organizations (for a full discussion on inclusion/exclusion criteria, click here). Data were collected between April 10-28, 2025. Of course, we cannot include all organizations (and employed individuals) working in this area, but aimed to include the most prominent. Their influence measure draws on the following metrics: social media followers; book popularity/impact; news attention; Congressional Record mentions; and Google search numbers. Then, in an approximation of the approach used by Hess of AEI in his annual rankings of university-based scholars which is posted by Education Week, we then calculated influence by totaling the social media following (divided by 1000), book popularity (divided by 10), news attention (divided by 10), Congressional Record mentions, and search results (divided by 10). The measure of expertise employs the following metrics: citation impact (or “h-index”); the number of non-fiction books published that were related to education; the number of education-related articles published in prestigious scholarly journals; and degree attainment. After multiplying the book and journal metrics by 2, these metrics were then added up to arrive at a measure of expertise. (For a full discussion of these metrics and methods, click here).

As noted, this year, we also examined the political leanings of the various organizations, and, by extension, the individuals who worked in those organizations. (Although we cannot know the specific political preferences of each individual, we categorized individuals by the politics of the organization in which they worked, under the assumption that individuals working in the policy space will typically work in organizations that generally align with their political values and, conversely, organizations will generally hire individuals who are aligned with their agenda.) For this, we drew on external websites and other independent efforts that categorize the political dispositions of such organizations (e.g., https://www.influencewatch.org; https://academicinfluence.com/inflection/study-guides/influential-think-tanks; Bland, 2020; Furnas et al., 2024: McGann, 2005). When such information was unavailable for a given think tank, members of our team individually examined their agenda, board, and funders, and then discussed which label was most appropriate. Essentially, these categories reflect differences in how organizations seek to preserve, adjust, or to more radically transform, the current school system in the US.

Beyond the addition of the political leanings measure, because this project was launched last year, we have since implemented some changes from last year’s rankings to better measure the issues of interest. These include:

- Adjustments to the list or organizations included in this exercise to reflect the emergence of new actors in this space (e.g., the America First Policy Institute), but also reflecting that some organizations no longer have individuals who were eligible for these rankings in light of our inclusion criteria.

- Updates to the names of organizations and individuals to include variants.

- Changes to inclusion criteria in order to better capture organizations and individuals active on these issues.

- Addition of Google search results as a measure of influence.

- Using BlueSky as an alternative when no X (Twitter) account was available.

- Averaging the results from three databases to determine news attention.

- Clarifying results to focus on education-related items in Amazon and Congressional Record searches.

- Expanding the lists of journals and book publishers included in the metrics.

Of course, we will look to refine our approach even more in the future, and are happy for suggestions in that regard.

Findings

When we look at the organizational level, in terms of influence, it is clear that the Manhattan Institute (MI) has — by far — the greatest impact on policy discussions, according to these metrics. Following Manhattan, AEI, New America, the Fordham Institute, and NPE round out the top 5 in terms of influence. The rankings for expertise present a somewhat different picture. Learning Policy Institute (LPI) ranks at the top, again, by a substantial margin. They are followed by Brookings, the Urban Institute, AEI, and New America. Thus, AEI appears near the top in both influence and expertise, whereas Manhattan’s top ranking in influence is not matched by its lower ranking in expertise.

Readers who are interested can get a deeper view into the factors by looking at our interactive data dashboard here. For example, from viewing the dashboard and underlying data, one can see that the Manhattan Institute’s high rankings in influence can be understood largely by its performance in two area. First, it has accumulated a huge social media following, followed on that measure by the Educational Freedom Institute (EFI), which has less than a quarter of the influence of MI in that aspect. MI also does quite well in book popularity, a close second to NPE on that measure, and in news attention, where it ranks just behind the leader in that metric: AEI. It is third in composite search results, but is much further down the list in Congressional mentions. Thus, MI’s position at the top of the influence rankings appears to be largely due to its outsized impact in social media, and its notable performance in terms of book popularity, news attention, and, to a lesser extent, in web searches.

When we look at the rankings of individuals at such organizations, we get a clearer understanding of Manhattan’s high influence ranking at the organizational level, but lower ranking in terms of organizational expertise.

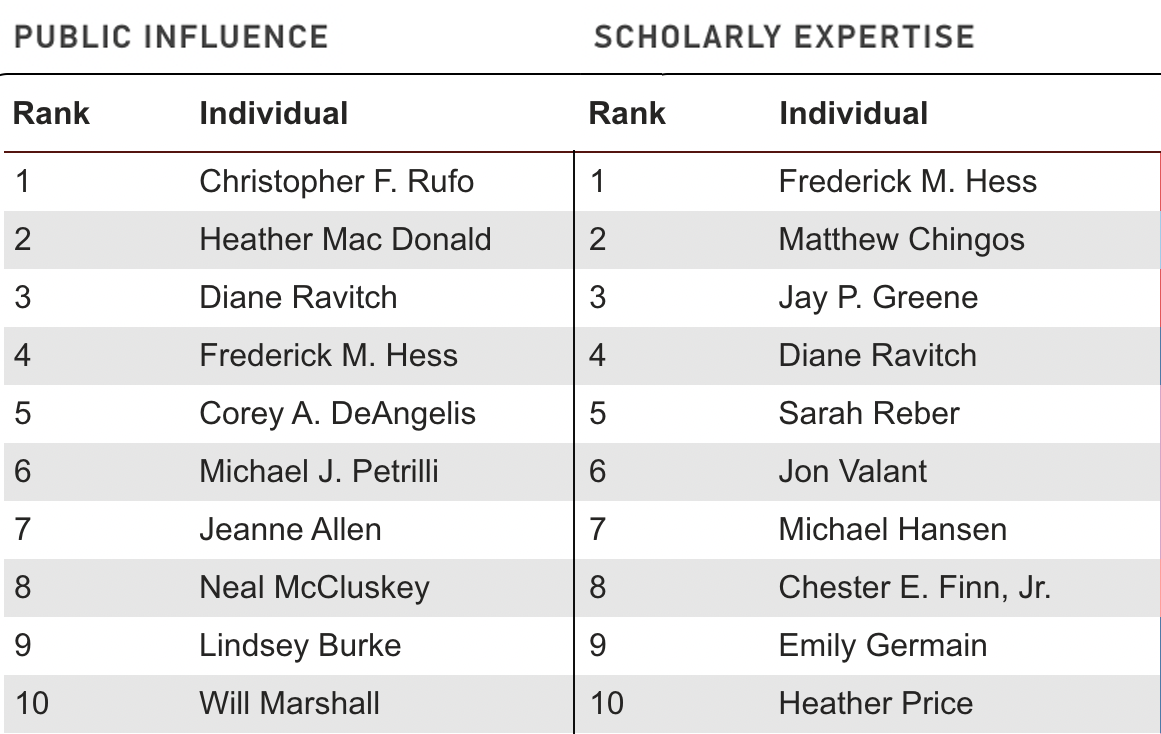

At the top of the individual rankings for influence — by far, as with the organizational rankings of influence — is Christopher Rufo, of the Manhattan Institute. He has more than twice the total score than the second-ranked individual, who is also at the Manhattan Institute (MI), suggesting that MI is good at hiring or nurturing influential individuals. Rounding out the top 5 individuals on the influence metric are Diane Ravitch (NPE), Rick Hess (AEI), and Corey DeAngelis (EFI). Only two of those individuals, however, were also highly ranked in terms of expertise. At the top of those rankings, Rick Hess (AEI), at number 1, was joined by Diane Ravitch (NPE), at number 3. This is a notable accomplishment, with these individuals successfully integrating their work as among the most influential and the most accomplished scholars on the list. None of the other top 10 most influential individuals appeared in the top ten in terms of scholarly expertise.

As we noted, this year, we also sought to provide some insights into the political leanings of the most influential and scholarly accomplished (expert) organizations and individuals. Drawing on independent classifications of the ideological predispositions of different organizations (and, by extension, individuals working in them), we labeled the entries in these rankings in one of 5 categories on the political spectrum, from liberal to conservative. In the rankings above these are indicated by the conventional color scheme of dark blue for the more liberal, to dark red for the more conservative.

Organizations generally considered to be conservative or centrist-conservative are well-represented in the rankings of influence, making up more than half of the top ranked organizations. Highly ranked conservative organizations in terms of influence metrics include Manhattan (1), AEI (2), Heritage (6), and EFI (8), along with the more centrist-conservative (by these classifications) Fordham and ExcelinEd (10). This pattern is more pronounced when we look at individuals working in education policy at these types of organizations, with 7 of the top ten most influential coming from conservative organizations, and an 8th is from a centrist-conservative organization.

But when we apply this same lens to expertise, we see a more ideologically balanced picture, both in terms of organizations and individuals. For organizations, 3 of the top 10 are conservative, 2 — including the top-ranked LPI — are liberal, 1 is centrist-conservative, 3 are centrist-liberal, and 1 we listed as centrist. A similar balance was seen in the individual rankings.

Conclusion

This year’s rankings highlight the notable success of more conservative organizations in influencing discussions on education policy issues, especially relative to their more modest level of expertise in some instances.

Rankings are popular because they are easy to understand, but they do not necessarily capture the full picture when issues are complex and involve many factors. This project is also limited in that way — it is not meant to be the final word on who the top education policy experts or think tanks are. Moreover, organizations’ influence is perpetually shifting, and we are merely providing ratings based on a particular time period; in the past four+ months, indeed, it could be argued that the 6th ranked Heritage Foundation’s (via their Project 2025 and Project Esther) influence in and beyond the education space has been profound and indeed unparalleled.

Still, comparing these rankings gives us an important glimpse into how disconnected policymaking can sometimes be in the US. For example, some of the most influential think tanks do not exhibit much discernible expertise, which raises questions about the empirical basis for their impactful contributions to policy discussions. These results may spark more questions — like what makes some organizations so powerful if not their expertise. Certainly, there are important dimensions related to addressing such questions — for example, factoring in think tanks’ funding sources and levels, organizational infrastructures, knowledge mobilization strategies, etc. — that remain underexplored. Hopefully, at least, these rankings will help start an overdue conversation about the role of think tanks and advocacy groups in shaping education policy.

References

Barham, J. (2023, October 16). Top Influential Think Tanks Ranked for 2024 | Academic Influence. https://academicinfluence.com/inflection/study-guides/influential-think-tanks

Bland, T. B. (2020). Predators and Principles: Think Tank Influence, Media Visibility, and Political Partisanship. Virginia Commonwealth University.

Furnas, A. C., LaPira, T. M., & Wang, D. (2024). Partisan Disparities in the Use of Science in Policy. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/aep9v

McGann, J. G. (2005). Think Tanks and Policy Advice in The US. Foreign Policy Research Institute.