Training Empathetic Teachers without Political Indoctrination?

Summary

Undergraduate pre-service teachers are required to take coursework in the social foundations of education. These courses are designed to expose students to systems of exclusion and bias and create a space for students to engage in introspection of their own dispositions and how those dispositions can inform their approach to teaching. Often policymakers are concerned that shifting student dispositions towards empathy can change political ideological stances. However, this is not the case.

The Perceived Political Landscape of Higher Education

Support for higher education among conservative America has waned in recent years because of perceived liberal bias censoring conservative students and unproven accusations of indoctrinating students into liberal ideology. This perception aligns with the growing, and manufactured, consternation surrounding conceptions of critical race theory (CRT) and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) being (or not being) taught in K-12 and college courses. These concerns are connected to fears that students will, because of liberal indoctrination, shift towards more liberal stances.

Rather than altering student political affiliation or informing how students should vote, the aim of courses that explore issues related to diversity is helping to develop students into well-rounded humans. This is important for students who are training for a career in education as exposing future teachers to data and conversations surrounding race, class, and equity can help reduce biases as new teachers enter schools. Implicit biases, when unexplored and unchallenged, can have incredibly negative implications for the classroom.

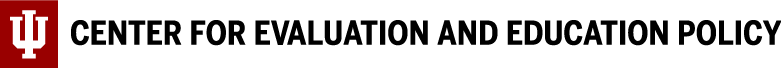

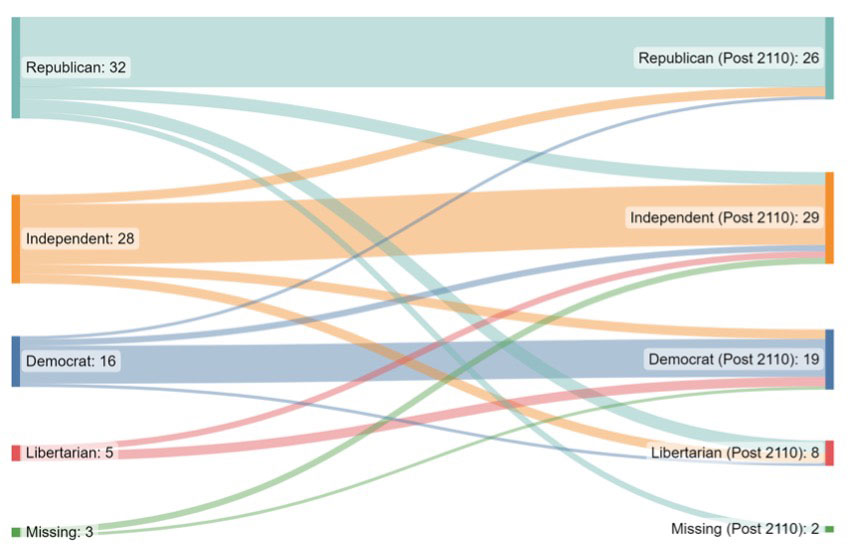

Considering the growing concern over universities being a bastion of liberal indoctrination, what impact, if any, does taking courses that include discussions on race, class, gender, etc., have on student ideological dispositions and political identity? Below is a brief overview of forthcoming work from a 5-year longitudinal study finding that pre-service teachers do, in fact, demonstrate significant shifts in their perceptions on race and class but, by-and-large, retain the self-reported political identity prior to the coursework.

Personal Growth, No Political Shifts

Prior to a class that explores the inequities across society and education, students held the view that society was equal and variance in education and societal outcomes could be explained simply by merit, work ethic, etc. This disposition can often lead to teachers assuming that students who struggle in a K-12 classroom due to a lack of resources simply do not want to work hard or that their race/culture is does not value education. Regardless of any policymaker’s political orientation, this negative attitude towards a student or group of students can facilitate negative educative experiences in the classroom.

As pre-service teacher coursework seeks to explore issues of implicit bias, the study showed that after exposure to information on race, class, gender, etc., and participating in thoughtful discussions throughout the term, students were less likely to attribute variance in socioeconomic and educational outcomes solely to merit. The data suggests that while students still believe that hard work is necessary to realize success, they recognize that the starting point is not the same for all demographics.

As the students in this study are largely first-generation, White, non-affluent students, the professors often approach conversations about inequity by discussing classism first. As these students are more easily able, and willing, to acknowledge class inequity given their less-than-affluent backgrounds; this not only opens the door for robust conversations that problematize notions of merit but, also, open the door for further conversations on intersectionality and how race and other lived experiences may exacerbate or ameliorate oppressive structures in society.

Much has been said about how conversations surrounding equity may aim to make White people feel guilty. Policy efforts in Florida have sought to restrict class discussions that might make White students feel bad. The data shows that social foundations of education courses have a dramatic and measurable impact on how students think about merit, class, and race, but also that developing that understanding did not result in a belief that they, themselves, were responsible for or guilty for structural racism. As states consider banning classroom conversations surrounding race out of a concern that White students will feel bad, educators and policymakers should understand that this idea are not supported by the data.

While a few students shifted their political thinking over time, the vast majority did not. Pre-service teachers who took social foundations of education courses continued to identify with the political identity documented prior to the coursework but expressed more empathetic dispositions towards non-White and non-affluent groups.

This brief is based on a manuscript in preparation by authors Brewer, T.J, McFaden, K., & Collier, D. (in preparation).

Authors

T. Jameson Brewer is an Associate Professor at the University of North Georgia

Kelly L. McFaden is a Professor at the University of North Georgia

Daniel A. Collier is an Assistant Professor of Higher and Adult Education at the University of Memphis

Edited by: Joseph Heisler, Center for Evaluation and Education Policy