Ranking Think Tanks in Education Policy: Impact, Expertise, and Ideology

Policy Brief #25-3 • June 2025

Summary

- Think tanks and similar organizations continue to play a prominent, even outsized role in education policy discussions.

- In many cases, there is an apparent disconnect between the influence of some organizations (and the individuals they employ) and the expertise they bring to the table.

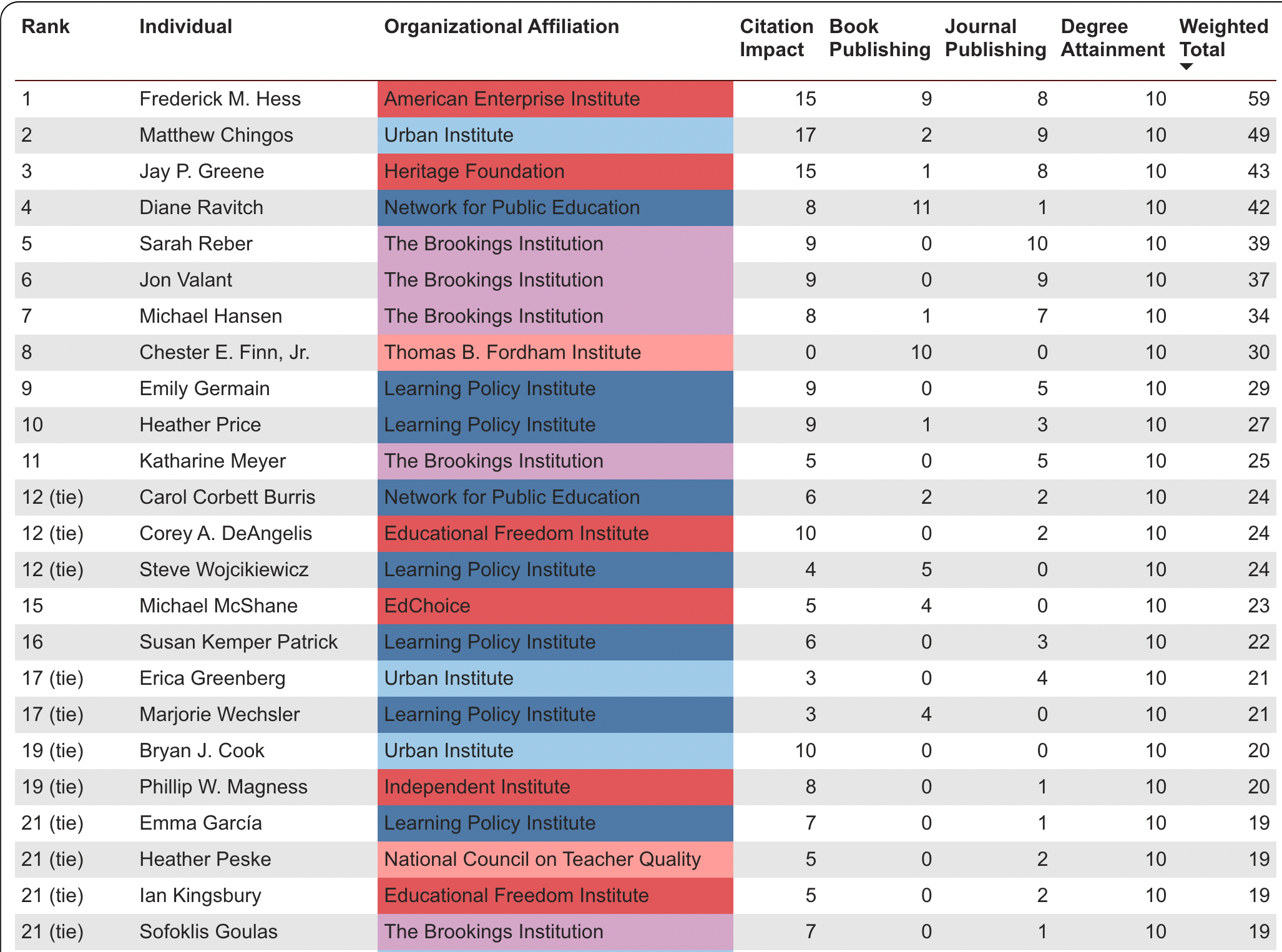

- Conservative-leaning organizations (and individuals therein) are well-represented at the top of the rankings of influence, while rankings of expertise show a more ideologically diverse picture.

Think tanks play an outsized role in policy discussions in the US, especially in education policy. While the term “think tank” would seem to imply that they serve as idea incubators and sources of new knowledge, our research suggests that quite often they instead serve as platforms for the promotion of pre-existing policy agendas rather than empirical enlightenment. Indeed, it is sometimes difficult if not impossible to distinguish think tanks from other advocacy organizations.

Our inaugural (2024) report on this issue highlighted the frequent disconnect between expertise and influence. Our findings illuminated how some organizations and individuals exert significant impact despite little or no research capacity, and, at the same time, others are skilled and immersed in empirical analysis of education issues, but have relatively little impact on policy discussions.

In this latest version of our annual ranking of think tanks and functionally similar organizations, we again examine the disproportionate influence some individuals and organizations exert relative to their expertise. But this new report adds another dimension. Here we also consider the political leanings of think tanks active on education policy issues, similar organizations, and the individuals who work for them.

The findings are quite revealing. In general, with some exceptions, of course, organizations associated with conservative agendas for education have tended to be the most successful in advancing their policy prescriptions, even when they have relatively less training and expertise on those topics. That is, they do quite well in the rankings of most influential organizations and individuals, but in many cases their notable ability in shaping policy discussions appears to be based less in evidence and analysis and more in successful advocacy. On the other hand, the rankings of education policy expertise illuminate a more ideologically diverse set of organizations and individuals. With some exceptions, liberal-leaning groups often have more expertise, but are less able to make an impact in policy discussions.

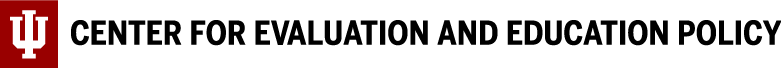

For example, as with our last report, we find a number of organizations — Manhattan Institute, AEI, New America, NPE and Heritage — topping the rankings of influence.

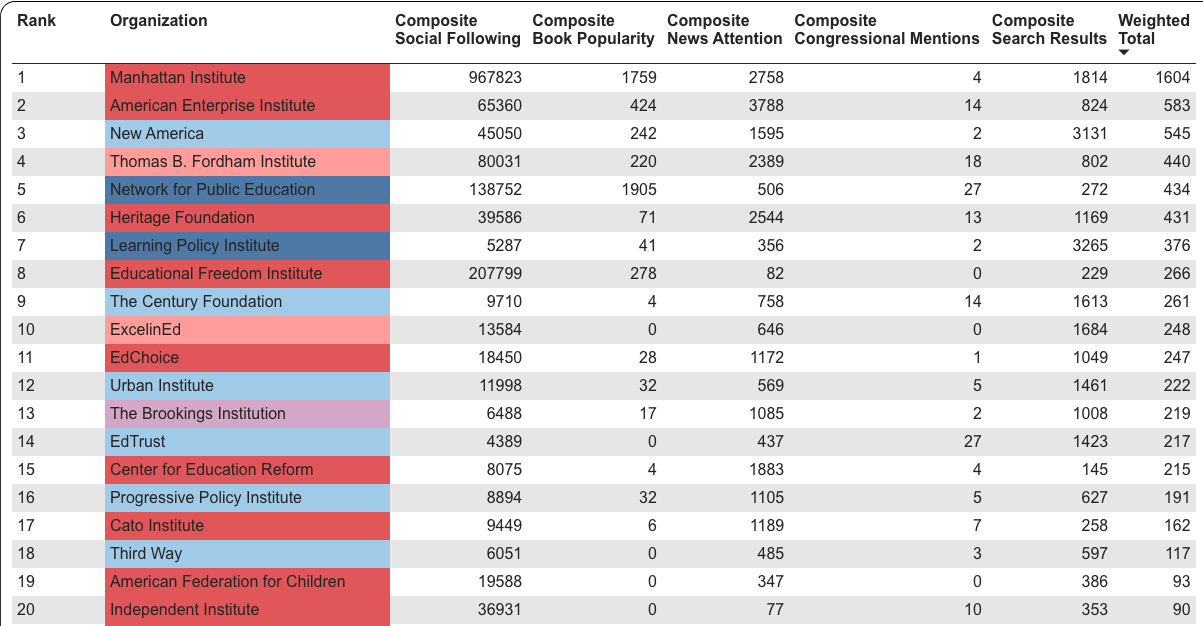

Some of those organizations, such as AEI and New America, also rank highly as far as the measures of expertise, indicating an appropriate confluence of factors that would appear to support evidence-based policy insights. But others ranking highly in influence, such as the Manhattan Institute, do not hold a commensurate rank when it comes to expertise.

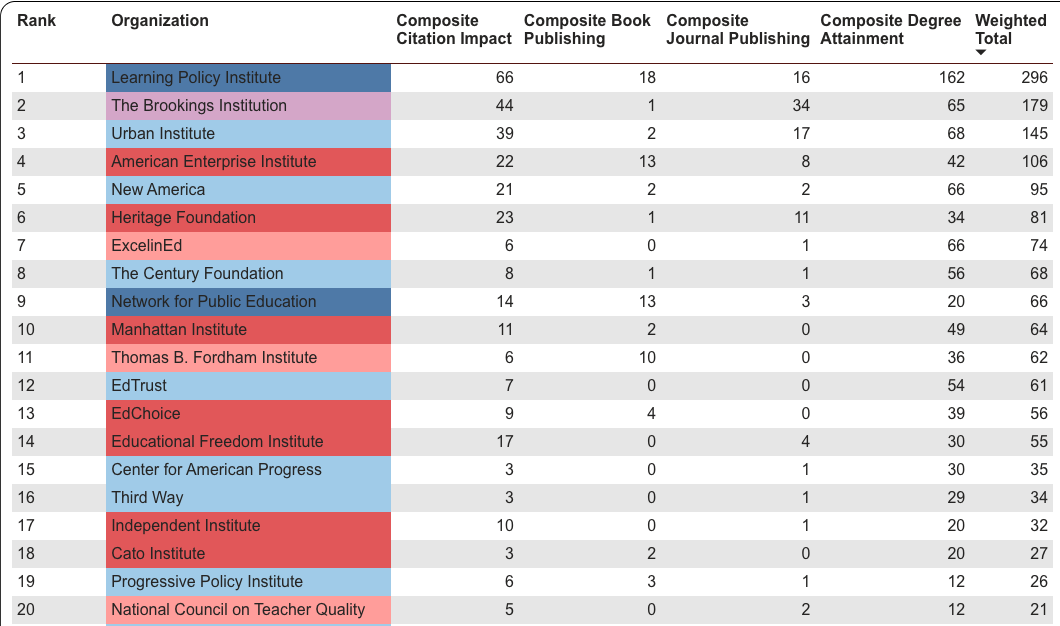

And we see similar issues when it comes to ranking individuals at such organizations, with Christopher Rufo at Manhattan Institute ranking — by far — at the top of the list of influence, but quite middling — tied for 122 out of 185 individuals — when it comes to expertise according to the metrics.

On the other hand, some organizations (such as AEI, New America, the Urban Institute, NPE, LPI) are at or near the top on both measures.

And when we consider the political leanings of organizations (and individuals at those organizations), another important factor emerges. Organizations generally considered to be conservative or centrist-conservative are well-represented in the ranking of influence, making up more than half of the highly ranked. This is more pronounced when we look at individuals working in education policy at these types of organizations, with 7 of the top ten most influential coming from conservative organizations, and an 8th from a centrist-conservative organization.

But when we apply this same lens to expertise, we see a more ideologically balanced picture, both in terms of organizations and individuals.

Conclusion

Of course, any exercise such as this is an inexact science, but is suggestive of patterns that are worth discussing. Indeed, our findings are based on particular measures and methodological decisions. We are transparent about those, and are happy to consider suggestions.

Nonetheless, these findings point to some potential concerns in an era where policymakers, philanthropists, and others are demanding “evidence-based” or “research-based” policy. When they demand to know “what works” for educating children, it is important to consider both the research acumen and ideological agendas of those seeking to shape education policy. Based on the findings in this analysis, there are reasons for concern that many of those supplying policymakers with agendas are more immersed in ideology than in empirical evidence.

This brief is based on the 2025 Edu-Thinker Influence and Expertise Rankings, which you can read more about HERE and view the full results and methods HERE.

Authors

Dr. Christopher Lubienski is a Professor of Education Policy at Indiana University Bloomington and Director of the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy.

Dr. Joel R. Malin is an Associate Professor in Educational Leadership at Miami University and a Fellow with CEEP.

Paul Faulkner is a PhD candidate in Education Policy Studies at Indiana University Bloomington.

Kristin Schumacher is a PhD student in Education Policy Studies at Indiana University Bloomington.