Are School Vouchers a Rural Issue?

Policy Brief #25-2 • May 2025

Summary

Recent claims that rural populations support vouchers are not reflected in voting patterns. Instead, obstacles to choice inherent in rural communities still seem to be an inherent obstacle to these programs, and their political support.

After years of trying, Texas Governor Greg Abbott was able to overcome opposition within the GOP to pass a school voucher program, which will be the largest in the country. Programs such as this, that use taxpayer dollars to send children to private schools, have also been recently approved or expanded in a number of states with large rural populations, including Iowa, Idaho, North Dakota, Utah, Georgia, and Indiana, and the Trump administration is positioned to expand vouchers across the US.

This is an important issue because, for years, many had seen school vouchers as a largely urban issue. Even though the Republican Party has been the champion of vouchers, this agenda didn’t appear to resonate in rural areas that lean heavily toward the GOP. This is for two reasons. First, dispersed rural communities generally have fewer opportunities to choose private schools, which tend to be concentrated in larger cities. But rural public schools also often serve a unique place and source of pride in their communities, whether due to high school sports or as one of the leading employers in the area.

But, with the passage of the Texas bill, some advocates are now arguing that rural reticence on school vouchers is a “myth.” If this is true, rural Republicans would not be an obstacle to the GOP’s efforts to expand vouchers nationwide, as they had been for years in Texas, where Abbott’s years-long effort to primary Republicans that opposed vouchers was funded largely by out-of-state mega donors.

As a case in point, a self-described “school choice evangelist” points to a list of rural states advancing voucher bills to argue that “rural voters are leading the charge” for school vouchers. But are they? After all, we know that, in general, voters overall tend to soundly reject school vouchers, often overwhelmingly, which is why these programs tend to get approved by lawmakers, not voters. Are rural voters an exception?

In arguing that rural voters want vouchers, this voucher advocate at the American Culture Project, points to three types of evidence: the number of rural states approving vouchers, a couple of surveys, and results from a past Texas GOP primary. His argument overstates support for vouchers among rural citizens – claiming that a survey indicates that 71% of rural Texans approve of vouchers, which is nearly ten points higher than what the survey actually shows. (Even then, the survey conflates “rural and semi-rural” counties into one category, which may overstate accurate sampling among rural Texans.) Of those who responded to the survey, the highest support for vouchers came from fundamentalist “born again” Christians (75%) who may favor defunding public schools in favor of subsidizing private religious education and homeschooling.

But rather than looking at survey participants and “rural” state legislation, a better way of understanding rural support for school voucher policies is to look at how voters actually vote on the issue.

In 2024, three states with large, rural populations voted on school vouchers and choice referenda. Although the specifics varied, voters in all these states — Kentucky, Colorado, and Nebraska — soundly rejected these measures, and even overturned policymakers’ efforts to impose vouchers in the latter case.

And when we drill down into votes across rural and urban communities, an interesting pattern emerges.

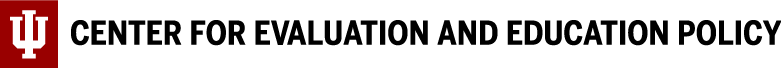

In Kentucky, voters were asked to approve an amendment that would enable lawmakers to send money to private schools. Overall, they rejected this by almost a 2 to 1 margin. But it wasn’t rejected only by urban voters in Louisville and Lexington. The measure failed in every one of Kentucky’s 120 counties — hardly “undeniable evidence” of rural voters’ hunger for vouchers.

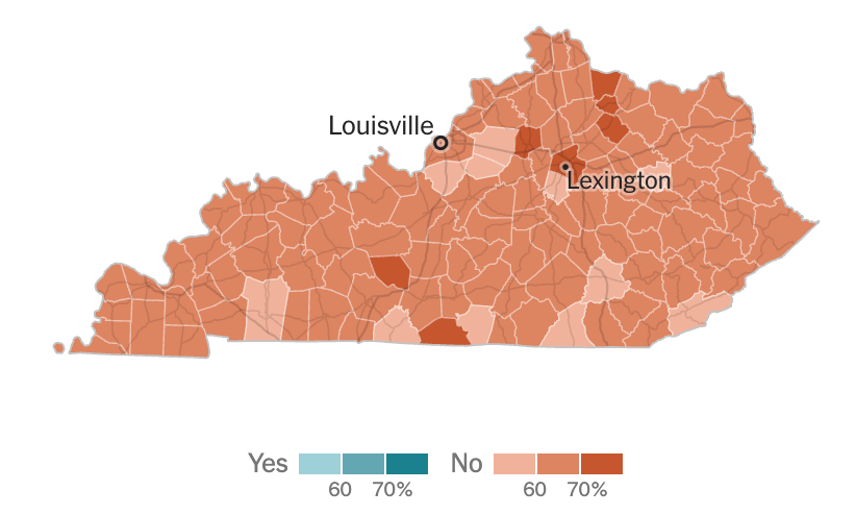

Colorado voters were asked to approve an amendment that would have created a constitutional right to school choice. The measure required 55% voter approval, but was supported by less than half the voters. It was rejected soundly in places like Denver and Boulder Counties, but also lost in dozens of smaller counties like Baca, Mineral, and Ouray. The measure was even defeated in places like conservative Douglas County (which has had its own voucher program).

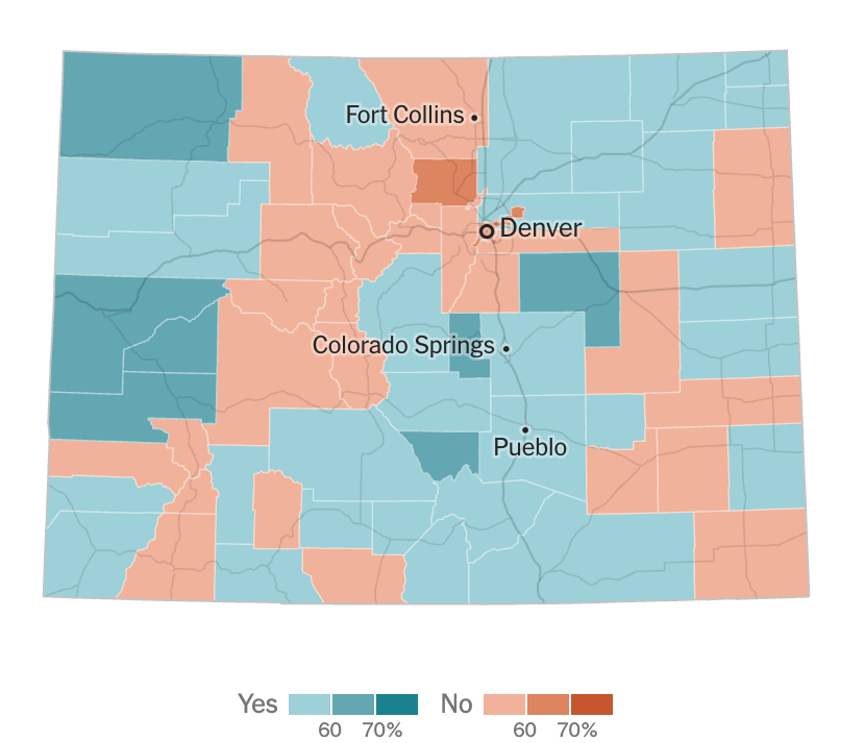

Perhaps most resoundingly, in Nebraska, 57% of all voters overturned their legislators’ attempt to create a voucher program. While voters in the three largest counties opposed vouchers, so too did voters in 79 of Nebraska’s other 90 counties. Even in the most rural counties, like Sioux County, with just a few hundred voters, lawmakers’ efforts to implement vouchers were overturned. Even in the 11 counties that voted to retain the program (which are not the least populated), no more than 54% of voters supported vouchers.

All in all, when it comes to voting, citizens (including those living in rural counties) have continued to oppose vouchers and voucher expansion. In nearly every case, the current pattern of voucher law passage has been the result of politician-driven efforts – often following ballot referendum rejections.

There are certainly important distinctions between voters, survey participants, and politicians. And simplistically pointing to polls and politicians is inadequate and even deceptive when trying to prove rural voters want vouchers when their actions speak otherwise — especially when poll results are misrepresented. But more importantly, this suggests a rural “red wall” opposing vouchers may exist if Washington tries to expand vouchers across the US, especially if voters have any say in the matter.

Authors

Christopher Lubienski is Director of the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy at Indiana University

T. Jameson Brewer is an Associate Professor of Social Foundations of Education at the University of North Georgia